Well, right up front I have to admit that coyotes do not really exist in Hawai'i, at least in the form that most of you know. Here they are much smaller and go by another name --

Herpestes Javanicus or "Mongoose" for short. I call them coyotes because they fill much the same ecological niche here as coyotes do on the mainland U.S.

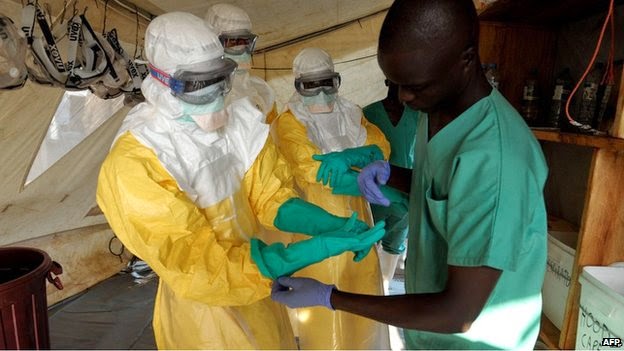

|

| Coyotus Konicus |

Although many visitors to Hawai'i assume mongooses are native to the islands, they are actually from India and Indonesia, and were deliberately introduced here in 1883 to control rats in the sugar cane fields.

Some initial success in the Carribean and West Indies with this method was reported in 1882 by naturalist W.B. Espeut. Espeut and others quickly began to raise mongooses and sell them commercially, including some to cane growers in Hawai'i (not all the islands, however). Unfortunately Espreut may have been a teensy bit premature in promoting the introduction of mongooses both here and elsewhere. Not only do we still have rats, the mongoose is now a very serious problem, as it is nearly everywhere else it has been introduced. In their authoritative book on mongooses, Dunn and Hinton describe the introduction of the mongoose into the West Indies as "...one of the most disastrous attempts ever made at biological control" (

Mongooses, p. 63), and the same is true here. The reasons for the failure are an important cautionary tale for those of us who live on islands, as we shall see.

The rat, too was introduced to Hawai'i but unintentionally --

one species coming with the Polynesian settlers about 1600 years ago and two others (the Black, or

Roof Rat and the

Norway Rat) with Europeans and Americans beginning in the late 18th century (

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Factsheet).

Espeut assumed that all rats are the same, as most of us do (you've seen one rat, you've seen them all, right?). Turns out the differences are very, very important. The Norway rat is a ground-nesting species whereas the other two nest in trees or high structures (the Polynesian and Roof rats). The mongoose is a

mediocre climber and so it was able to prey on the Norway rat but had much more difficulty with the other two. In a number of studies

scientists have found that the introduction of mongoose has led to a decrease in Norway rats but increases in the other two varieties. The often-quoted story that the mongoose didn't control rats in Hawai'i because the mongoose is active during the day whereas rats are active at night is a

gross oversimplification -- the mongoose was able to find the nests of the Norway rat and destroy them even during the day, but it couldn't reach the other two, day or night.

Espeut also underestimated the breeding ability of rats, which far outstrips predation by mongooses. Further, after reducing the numbers of Norway rats, mongoose then go after other sources of food, including the eggs of ground-nesting birds, beneficial lizards, snakes (none in Hawai'i) and amphibians. And there are no natural predators in Hawai'i to keep the populations of mongoose in check.

Both the mongoose and the rat were introduced to Hawai'i and are clearly new arrivals here. In fact, prior to the arrival of humans in the Hawaiian Islands there

only two species of endemic mammals -- the Monk Seal and the Hawaiian Bat. The Polynesians intentionally brought two more (besides themselves, of course): a small domesticated pig and a small variety of dog. All the rest have been brought here intentionally or accidentally in the last 200+ years -- the blink of an eye in geological and evolutionary time. While it is true that everything here came from somewhere else, the rate of introduction is crucial to understanding the ecological impact these introductions have had and to appreciating those things that are truly unique here.

The Hawaiian Islands are the most isolated group of islands in the world. Their isolation has meant that the species of plants and animals that managed to arrive here on their own from other parts of the world were themselves isolated from that time on and evolved over eons into unique forms. For instance we have raspberry vines here but they don't have thorns because they no longer needed them as defense against browsing mammals. Almost all endemic Hawaiian birds evolved from a single species of honey creeper and are found nowhere else on earth. Certain trees, like the Ohia, evolved in the presence of almost continuous volcanic activity and are able to withstand and even thrive in conditions that would kill many others.

Most people who visit Hawai'i see a lush and colorful landscape that, though exotic, still seems somewhat

|

| Java Sparrows (Introduced 1960's) |

|

| Safron Finch (SA, introduced 1960's) | |

familiar. This is because many of the plants, animals, birds, and insects are in fact not from Hawai'i at all but from the mainland U.S., South America, Europe, and Asia. For example, nearly all of the colorful birds people see (including

parrots, turkeys, pheasants, and various songbirds) came from elsewhere, many within the past 200 years or less.

At my house I occasionally see two endemic bird species, the I'o and

the Pu'eo (native hawks and owls, respectively). That's it. There are, however many cute introduced birds in my neighborhood, like the Saffron Finch from South America and the Java Sparrow from Indonesia, both introduced in the 1960's. There

were dozens more native birds but they are either now extinct or are only

found in remote areas, usually at much higher elevations than most

tourists go (an exception is Volcanoes National Park where a number of native birds can be seen).

Many of the less attractive aspects of Hawai'i also are not original. Here's a partial list of negative critters that were NOT in Hawai'i before their recent introduction by humans:

- rats

- mice

- cockroaches

- ants

- mosquitos

- termites

- wasps (Yellow Jacket variety)

- giant centipedes

- slugs

Looking at the list above, it is clear how we use our past experiences with the world to shape our expectations and interpretations of what we encounter in new places. Nearly all of us have lived where pests like rats, ants and mosquitos are a natural and common aspect of our environment and so we are not surprised when they exist here in Hawai'i also. The real surprise is that this was a place not long ago where they did

not exist. Imagine -- no rats, mice, mosquitoes, ants, or cockroaches! And of course the sad fact is that they wouldn't be here now if it weren't for

us.

Our past experiences can also lead us astray when we assess the implications of what we see in a new environment. This is particularly true for Hawai'i's isolated and uniquely fragile environment. For instance, many of those beautiful birds I mentioned are considered by biologists to be serious problems here because although they are in ecological balance in their original habitats, they become an

invasive species when they are introduced to Hawai'i. Relying on our preference for their attractiveness or their benign role elsewhere as the basis for judging their desirability in Hawaii's environment can be a very bad mistake.

To call something invasive isn't the same as using other negative terms, like referring to a particular plant as a "weed." Weeds are often simply something we deem undesirable based on aesthetic preference. An "invasive species" is something that meets one or more of a number of specific scientific criteria, including:

- being able to spread quickly and widely

- being either a predator that threatens to extinguish beneficial native species or having qualities that give it competitive superiority over other species for food or territory

- altering the habitat in unsustainable ways

- producing significant negative impact on the local economy

Of course, values and attitudes are still at play when we decide

what action, if any, should be taken to control invasive species. This is particularly true when the species is something we find beautiful or cute, like most of the small birds we have introduced, or a species we find desirable in other ways, like the animals brought here to be hunted for food or sport.

An instructive comparison is between a variety of

wild turkey introduced here in 1961 versus the

Nene, an endemic variety of goose and the Hawai'i state bird. Both are large, ground-nesting and foraging birds that prefer not to fly much but are magnificent when they do. The

Nene is severely endangered, whereas the wild turkey has increased from

400 birds to 16,000 in just 50 years (there

|

| Latest introduction 1960's |

are actually several varieties of turkeys in Hawai'i, all of them intentionally introduced beginning in the late 1700's and 1800's). In its original environment of North America the wild turkey's numbers are kept in balance by several predators (fox, coyotes, cougars, large birds of prey, skunks, bobcats, racoons, possum, and snakes), harsh winters, and hunting by humans. Being a prey animal living in harsh conditions, it evolved a number of characteristics to counter these threats: (1) it has large number of offspring, 10-14 chicks; (2) it is polygamous, with the males establishing large harems of females during mating season; (3) it eats almost anything -- leaves, fruit, seeds, and nuts of a wide variety of plants, shrubs, and trees, insects of various kinds, even small amphibians and lizards, (4) it takes refuge in trees at night to avoid predators; (5) it has developed resistance to many diseases carried by other mainland birds and animals. Without the controlling influences in the turkey's original environment, these qualities can be very ecologically problematic in Hawai'i where there are far fewer predators, a very benign climate, few competitors, and plenty of food.

The Nene, on the other hand, evolved in the absence of all the predators listed above with the exception of birds of prey, and without the ecological competition of other foraging birds (recall,

|

| Nene -- Endemic |

most other birds were types of honey-creepers). It has fewer offpring, 1-5 per female, tends to be monogamous (often mating for life), is a selective and somewhat picky eater of leaves, seeds and berries and has no immunity to diseases carried by birds and animals recently introduced. These qualities were adaptive for the environment that existed before the arrival of humans and the introduction of predators and generalist competitors. But Nene are poorly equipped to handle these sudden changes, and only through an aggressive captive breeding program have they been brought back from the brink of extinction. People often see Nene in open grasslands, like golf-courses, and incorrectly assume they are plentiful. Visitors mistakenly believe them to be Canadian Geese, from which they evolved starting about 500,000 years ago, and which have become a serious nuisance in urban areas of the mainland where they congregate in large numbers -- another example of how past experience can sometimes lead to wrong conclusions in new environments.

The

natural introduction of a new species causes an imbalance in an existing ecosystem that in time will sort itself out. In the case of Hawai'i

new plants, animals and insects arrived at a relatively slow pace due to the isolation of the islands. However, beginning with the arrival of humans 1,600 years ago and accelerating tremendously with Cook's discovery of the islands a little over 200 years ago, hundreds of new species of plants, animals, insects, and diseases have been introduced within a very short time. And the ecosystem is still in turmoil, according to biologists who are studying this process and who find Hawai'i a fascinating and valuable natural laboratory to observe both ecological adaptation and evolution in action. The biologists naturally and understandably stress the negative impact new species have had on native populations but they are also intrigued by how these new species interact

with each other and in some cases how native species have adapted in positive ways to the newcomers.

|

| Apapane -- Endemic |

For example, the Pue'o (endemic owl) and the I'o (endemic hawk) never saw a rat or a mouse until their recent introduction. Their diet consisted mainly of other native

birds. Now, however, they are learning that these new furry critters are a tasty source of protein. They also are quite happy to eat

introduced birds, particularly now that the native varieties are scarce. Another example is that one species of endemic bird, the beautiful

Apapane, is apparently developing a resistance to Avian Malaria that is carried by alien birds -- this disease, transmitted by mosquitoes that breed in terrain uprooted by European wild boars, has decimated many native Hawaiian species. As I said, evolution in action.

There are also examples of new arrivals controlling

each other. Mongoose, rats, and feral cats -- justly demonized for preying on native birds -- are now major controllers of burgeoning populations of introduced birds that would otherwise become an even greater destructive problem than they are now. This is why I call the Mongoose a Kona Coyote -- in this environment it performs a controlling role similar to the coyote on the mainland U.S.. Although mongoose, rats and feral cats are themselves a

serious problem, if they were to be suddenly eradicated in Hawai'i the populations of introduced bird species would skyrocket, with severely negative consequences.

Note that this is another illustration of how our prior experiences can lead us astray in new situations. Many of us from the mainland U.S. are very familiar with the negative impact of cats on bird populations there. But in that case the birds are not alien and not invasive. Of course, eradicating introduced birds in Hawai'i would likely also cause problems. For instance, the

Myna bird from Southeast Asia has become very fond of eating

geckos from Madagascar, which aside from humans and cats have no other predators here and are very prolific breeders.

These examples illustrate the complexity of the mess we have created and the fact that solutions can't be as simple as we often assume -- some approaches will just make matters worse here in Hawai'i even though they might be appropriate elsewhere. And since rolling back the clock isn't really possible, we are left with developing ways to substitute the control forces that are absent for the species we have introduced, an expensive and risky proposition given our historical record in this matter (remember the lesson from the curious case of the Kona Coyote).

If you look back at the list of qualities for defining an invasive species you might agree that humans fit nearly all of them. We are able to spread quickly and widely over most of the planet. We are a predator that

threatens to extinguish beneficial native species. We have qualities

that give us competitive superiority over other species for food and territory. And we certainly have a record of altering the habitat in unsustainable ways. A key difference between us and other invasive species, however, is that we are aware of what we are doing and we can alter our behavior and mitigate the effects of our own presence as well as the effects of those species we have introduced either intentionally or unintentionally.

The question is whether we have the will to do so. And whether we still have time.

__________________________________

Some Resources and References:

Hawai'i's Invasive Species, 2001. Staples, G.W. & Cowie, R.H. (Eds.). Mutual Publishing, Honolulu.

"Invasive Species" U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Encyclopedia of Invasive Species: From Africanized Honey Bees to Zebra Mussels by Susan L. Woodward & Joyce A. Quinn

Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions - edited by Daniel Simberloff & Marcel Rejmanek

Biological Control by H.M.T. Hokkanen & James M. Lynch

Fighting Invasive Species in Hawai'i The Nature Conservancy

Invasive Species in Hawai'i University of Hawa'i'

Mongooses by A. M. S. Dunn &

H. E. Hinton

Other Blogs in the "Critters of Hawai'i series:

Tons of Fun

"Lei"zy Horses and Hot Malasadas

More Than You Ever Wanted To Know About Geckos